Electron configuration

In atomic physics and quantum chemistry, electron configuration is the arrangement of electrons of an atom, a molecule, or other physical structure.[1] It concerns the way electrons can be distributed in the orbitals of the given system (atomic or molecular for instance).

Like other elementary particles, the electron is subject to the laws of quantum mechanics, and exhibits both particle-like and wave-like nature. Formally, the quantum state of a particular electron is defined by its wave function, a complex-valued function of space and time. According to the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, the position of a particular electron is not well defined until an act of measurement causes it to be detected. The probability that the act of measurement will detect the electron at a particular point in space is proportional to the square of the absolute value of the wavefunction at that point.

An energy is associated with each electron configuration and, upon certain conditions, electrons are able to move from one orbital to another by emission or absorption of a quantum of energy, in the form of a photon.

Knowledge of the electron configuration of different atoms is useful in understanding the structure of the periodic table of elements. The concept is also useful for describing the chemical bonds that hold atoms together. In bulk materials this same idea helps explain the peculiar properties of lasers and semiconductors.

Contents |

Shells and subshells

Electron configuration was first conceived of under the Bohr model of the atom, and it is still common to speak of shells and subshells despite the advances in understanding of the quantum-mechanical nature of electrons.

An electron shell is the set of allowed states electrons may occupy which share the same principal quantum number, n (the number before the letter in the orbital label). An atom's nth electron shell can accommodate 2n2 electrons, e.g. the first shell can accommodate 2 electrons, the second shell 8 electrons, and the third shell 18 electrons. The factor of two arises because the allowed states are doubled due to electron spin—each atomic orbital admits up to two otherwise identical electrons with opposite spin, one with a spin +1/2 (usually noted by an up-arrow) and one with a spin -1/2 (with a down-arrow).

A subshell is the set of states defined by a common azimuthal quantum number, l, within a shell. The values l = 0, 1, 2, 3 correspond to the s, p, d, and f labels, respectively. The maximum number of electrons which can be placed in a subshell is given by 2(2l + 1). This gives two electrons in an s subshell, six electrons in a p subshell, ten electrons in a d subshell and fourteen electrons in an f subshell.

The numbers of electrons that can occupy each shell and each subshell arise from the equations of quantum mechanics,[2] in particular the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that no two electrons in the same atom can have the same values of the four quantum numbers.[3]

Notation

Physicists and chemists use a standard notation to indicate the electron configurations of atoms and molecules. For atoms, the notation consists of a sequence of atomic orbital labels (e.g. for phosphorus the sequence 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p) with the number of electrons assigned to each orbital (or set of orbitals sharing the same label) placed as a superscript. For example, hydrogen has one electron in the s-orbital of the first shell, so its configuration is written 1s1. Lithium has two electrons in the 1s-subshell and one in the (higher-energy) 2s-subshell, so its configuration is written 1s2 2s1 (pronounced "one-s-two, two-s-one"). Phosphorus (atomic number 15), is as follows: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p3.

For atoms with many electrons, this notation can become lengthy and so an abbreviated notation is used, since all but the last few subshells are identical to those of one or another of the noble gases. Phosphorus, for instance, differs from neon (1s2 2s2 2p6) only by the presence of a third shell. Thus, the electron configuration of neon is pulled out, and phosphorus is written as follows: [Ne] 3s2 3p3. This convention is useful as it is the electrons in the outermost shell which most determine the chemistry of the element.

The order of writing the orbitals is not completely fixed: some sources group all orbitals with the same value of n together, while other sources (as here) follow the order given by Madelung's rule. Hence the electron configuration of iron can be written as [Ar] 3d6 4s2 (keeping the 3d-electrons with the 3s- and 3p-electrons which are implied by the configuration of argon) or as [Ar] 4s2 3d6 (following the Aufbau principle, see below).

The superscript 1 for a singly-occupied orbital is not compulsory.[4] It is quite common to see the letters of the orbital labels (s, p, d, f) written in an italic or slanting typeface, although the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) recommends a normal typeface (as used here). The choice of letters originates from a now-obsolete system of categorizing spectral lines as "sharp", "principal", "diffuse" and "fundamental", based on their observed fine structure: their modern usage indicates orbitals with an azimuthal quantum number, l, of 0, 1, 2 or 3 respectively. After "f", the sequence continues alphabetically "g", "h", "i"... (l = 4, 5, 6...), skipping "j", although orbitals of these types are rarely required.

The electron configurations of molecules are written in a similar way, except that molecular orbital labels are used instead of atomic orbital labels (see below).

Energy — ground state and excited states

The energy associated to an electron is that of its orbital. The energy of a configuration is often approximated as the sum of the energy of each electron, neglecting the electron-electron interactions. The configuration that corresponds to the lowest electronic energy is called the ground state. Any other configuration is an excited state.

As an example, the ground state configuration of the sodium atom is 1s22s22p63s, as deduced from the Aufbau principle (see below). The first excited state is obtained by promoting a 3s electron to the 3p orbital, to obtain the 1s22s22p63p configuration, abbreviated as the 3p level. Atoms can move from one configuration to another by absorbing or emitting energy. In a sodium-vapor lamp for example, sodium atoms are excited to the 3p level by an electrical discharge, and return to the ground state by emitting yellow light of wavelength 589 nm.

Usually the excitation of valence electrons (such as 3s for sodium) involves energies corresponding to photons of visible or ultraviolet light. The excitation of core electrons is possible, but requires much higher energies generally corresponding to x-ray photons. This would be the case for example to excite a 2p electron to the 3s level and form the excited 1s22s22p53s2 configuration.

The remainder of this article deals only with the ground-state configuration, often referred to as "the" configuration of an atom or molecule.

History

Niels Bohr was the first to propose (1923) that the periodicity in the properties of the elements might be explained by the electronic structure of the atom.[5] His proposals were based on the then current Bohr model of the atom, in which the electron shells were orbits at a fixed distance from the nucleus. Bohr's original configurations would seem strange to a present-day chemist: sulfur was given as 2.4.4.6 instead of 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p4 (2.8.6).

The following year, E. C. Stoner incorporated Sommerfeld's third quantum number into the description of electron shells, and correctly predicted the shell structure of sulfur to be 2.8.6.[6] However neither Bohr's system nor Stoner's could correctly describe the changes in atomic spectra in a magnetic field (the Zeeman effect).

Bohr was well aware of this shortcoming (and others), and had written to his friend Wolfgang Pauli to ask for his help in saving quantum theory (the system now known as "old quantum theory"). Pauli realized that the Zeeman effect must be due only to the outermost electrons of the atom, and was able to reproduce Stoner's shell structure, but with the correct structure of subshells, by his inclusion of a fourth quantum number and his exclusion principle (1925):[7]

It should be forbidden for more than one electron with the same value of the main quantum number n to have the same value for the other three quantum numbers k [l], j [ml] and m [ms].

The Schrödinger equation, published in 1926, gave three of the four quantum numbers as a direct consequence of its solution for the hydrogen atom:[2] this solution yields the atomic orbitals which are shown today in textbooks of chemistry (and above). The examination of atomic spectra allowed the electron configurations of atoms to be determined experimentally, and led to an empirical rule (known as Madelung's rule (1936),[8] see below) for the order in which atomic orbitals are filled with electrons.

Aufbau principle and Madelung rule

The Aufbau principle (from the German Aufbau, "building up, construction") was an important part of Bohr's original concept of electron configuration. It may be stated as:[9]

- a maximum of two electrons are put into orbitals in the order of increasing orbital energy: the lowest-energy orbitals are filled before electrons are placed in higher-energy orbitals.

The principle works very well (for the ground states of the atoms) for the first 18 elements, then decreasingly well for the following 100 elements. The modern form of the Aufbau principle describes an order of orbital energies given by Madelung's rule (or Klechkowski's rule). This rule was first stated by Charles Janet in 1929, rediscovered by Erwin Madelung in 1936,[8]and later given a theoretical justification by V.M. Klechkowski[10]

-

- Orbitals are filled in the order of increasing n+l;

- Where two orbitals have the same value of n+l, they are filled in order of increasing n.

This gives the following order for filling the orbitals:

- 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, 7s, 5f, 6d, and 7p

The Aufbau principle can be applied, in a modified form, to the protons and neutrons in the atomic nucleus, as in the shell model of nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry.

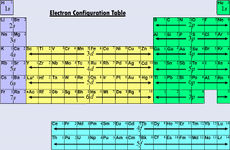

The periodic table

The form of the periodic table is closely related to the electron configuration of the atoms of the elements. For example, all the elements of group 2 have an electron configuration of [E] ns2 (where [E] is an inert gas configuration), and have notable similarities in their chemical properties. The outermost electron shell is often referred to as the "valence shell" and (to a first approximation) determines the chemical properties. It should be remembered that the similarities in the chemical properties were remarked more than a century before the idea of electron configuration,[11] It is not clear how far Madelung's rule explains (rather than simply describes) the periodic table,[12] although some properties (such as the common +2 oxidation state in the first row of the transition metals) would obviously be different with a different order of orbital filling.

Shortcomings of the Aufbau principle

The Aufbau principle rests on a fundamental postulate that the order of orbital energies is fixed, both for a given element and between different elements: neither of these is true (although they are approximately true enough for the principle to be useful). It considers atomic orbitals as "boxes" of fixed energy into which can be placed two electrons and no more. However the energy of an electron "in" an atomic orbital depends on the energies of all the other electrons of the atom (or ion, or molecule, etc.). There are no "one-electron solutions" for systems of more than one electron, only a set of many-electron solutions which cannot be calculated exactly[13] (although there are mathematical approximations available, such the Hartree–Fock method).

The fact that the Aufbau principle is based on an approximation can be seen from the fact that there is an almost-fixed filling order at all, that, within a given shell, the s-orbital is always filled before the p-orbitals. In a hydrogen-like atom, which only has one electron, the s-orbital and the p-orbitals of the same shell have exactly the same energy, to a very good approximation in the absence of external electromagnetic fields. (However, in a real hydrogen atom, the energy levels are slightly split by the magnetic field of the nucleus, and by the quantum electrodynamic effects of the Lamb shift).

Ionization of the transition metals

The naive application of the Aufbau principle leads to a well-known paradox (or apparent paradox) in the basic chemistry of the transition metals. Potassium and calcium appear in the periodic table before the transition metals, and have electron configurations [Ar] 4s1 and [Ar] 4s2 respectively, i.e. the 4s-orbital is filled before the 3d-orbital. This is in line with Madelung's rule, as the 4s-orbital has n+l = 4 (n = 4, l = 0) while the 3d-orbital has n+l = 5 (n = 3, l = 2). However, chromium and copper have electron configurations [Ar] 3d5 4s1 and [Ar] 3d10 4s1 respectively, i.e. one electron has passed from the 4s-orbital to a 3d-orbital to generate a half-filled or filled subshell. In this case, the usual explanation is that "half-filled or completely-filled subshells are particularly stable arrangements of electrons".

The apparent paradox arises when electrons are removed from the transition metal atoms to form ions. The first electrons to be ionized come not from the 3d-orbital, as one would expect if it were "higher in energy", but from the 4s-orbital. The same is true when chemical compounds are formed. Chromium hexacarbonyl can be described as a chromium atom (not ion, it is in the oxidation state 0) surrounded by six carbon monoxide ligands: it is diamagnetic, and the electron configuration of the central chromium atom is described as 3d6, i.e. the electron which was in the 4s-orbital in the free atom has passed into a 3d-orbital on forming the compound. This interchange of electrons between 4s and 3d is universal among the first series of the transition metals.[14]

The phenomenon is only paradoxical if it is assumed that the energies of atomic orbitals are fixed and unaffected by the presence of electrons in other orbitals. If that were the case, the 3d-orbital would have the same energy as the 3p-orbital, as it does in hydrogen, yet it clearly doesn't. There is no special reason why the Fe2+ ion should have the same electron configuration as the chromium atom, given that iron has two more protons in its nucleus than chromium and that the chemistry of the two species is very different. When care is taken to compare "like with like", the paradox disappears.[15]

Other exceptions to Madelung's rule

There are several more exceptions to Madelung's rule among the heavier elements, and it is more and more difficult to resort to simple explanations such as the stability of half-filled subshells. It is possible to predict most of the exceptions by Hartree–Fock calculations,[16] which are an approximate method for taking account of the effect of the other electrons on orbital energies. For the heavier elements, it is also necessary to take account of the effects of Special Relativity on the energies of the atomic orbitals, as the inner-shell electrons are moving at speeds approaching the speed of light. In general, these relativistic effects[17] tend to decrease the energy of the s-orbitals in relation to the other atomic orbitals.[18]

| Period 5 | Period 6 | Period 7 | ||||||||

| Element | Z | Electron Configuration | Element | Z | Electron Configuration | Element | Z | Electron Configuration | ||

| Lanthanum | 57 | [Xe] 6s2 5d1 | Actinium | 89 | [Rn] 7s2 6d1 | |||||

| Cerium | 58 | [Xe] 6s2 4f1 5d1 | Thorium | 90 | [Rn] 7s2 6d2 | |||||

| Praseodymium | 59 | [Xe] 6s2 4f3 | Protactinium | 91 | [Rn] 7s2 5f2 6d1 | |||||

| Neodymium | 60 | [Xe] 6s2 4f4 | Uranium | 92 | [Rn] 7s2 5f3 6d1 | |||||

| Promethium | 61 | [Xe] 6s2 4f5 | Neptunium | 93 | [Rn] 7s2 5f4 6d1 | |||||

| Samarium | 62 | [Xe] 6s2 4f6 | Plutonium | 94 | [Rn] 7s2 5f6 | |||||

| Europium | 63 | [Xe] 6s2 4f7 | Americium | 95 | [Rn] 7s2 5f7 | |||||

| Gadolinium | 64 | [Xe] 6s2 4f7 5d1 | Curium | 96 | [Rn] 7s2 5f7 6d1 | |||||

| Terbium | 65 | [Xe] 6s2 4f9 | Berkelium | 97 | [Rn] 7s2 5f9 | |||||

| Yttrium | 39 | [Kr] 5s2 4d1 | Lutetium | 71 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d1 | Lawrencium | 103 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 7p1 | ||

| Zirconium | 40 | [Kr] 5s2 4d2 | Hafnium | 72 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d2 | Rutherfordium | 104 | (unknown) | ||

| Niobium | 41 | [Kr] 5s1 4d4 | Tantalium | 73 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d3 | |||||

| Molybdenum | 42 | [Kr] 5s1 4d5 | Tungsten | 74 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d4 | |||||

| Technetium | 43 | [Kr] 5s2 4d5 | Rhenium | 75 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d5 | |||||

| Ruthenium | 44 | [Kr] 5s1 4d7 | Osmium | 76 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d6 | |||||

| Rhodium | 45 | [Kr] 5s1 4d8 | Iridium | 77 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d7 | |||||

| Palladium | 46 | [Kr] 4d10 | Platinum | 78 | [Xe] 6s1 4f14 5d9 | |||||

| Silver | 47 | [Kr] 5s1 4d10 | Gold | 79 | [Xe] 6s1 4f14 5d10 | |||||

| Cadmium | 48 | [Kr] 5s2 4d10 | Mercury | 80 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d10 | |||||

| Indium | 49 | [Kr] 5s2 4d10 5p1 | Thallium | 81 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d10 6p1 | |||||

By the Madelung rule, 103 Lawrencium would be an expected *[Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d1. The electron-shell configuration of heavier elements is not yet known.

Electron configuration in molecules

In molecules, the situation becomes more complex, as each molecule has a different orbital structure. The molecular orbitals are labelled according to their symmetry,[19] rather than the atomic orbital labels used for atoms and monoatomic ions: hence, the electron configuration of the dioxygen molecule, O2, is 1σg2 1σu2 2σg2 2σu2 1πu4 3σg2 1πg2.[1] The term 1πg2 represents the two electrons in the two degenerate π*-orbitals (antibonding). From Hund's rules, these electrons have parallel spins in the ground state, and so dioxygen has a net magnetic moment (it is paramagnetic). The explanation of the paramagnetism of dioxygen was a major success for molecular orbital theory.

Electron configuration in solids

In a solid, the electron states become very numerous. They cease to be discrete, and effectively blend into continuous ranges of possible states (an electron band). The notion of electron configuration ceases to be relevant, and yields to band theory.

Applications

The most widespread application of electron configurations is in the rationalization of chemical properties, in both inorganic and organic chemistry. In effect, electron configurations, along with some simplified form of molecular orbital theory, have become the modern equivalent of the valence concept, describing the number and type of chemical bonds that an atom can be expected to form.

This approach is taken further in computational chemistry, which typically attempts to make quantitative estimates of chemical properties. For many years, most such calculations relied upon the "linear combination of atomic orbitals" (LCAO) approximation, using an ever larger and more complex basis set of atomic orbitals as the starting point. The last step in such a calculation is the assignment of electrons among the molecular orbitals according to the Aufbau principle. Not all methods in calculational chemistry rely on electron configuration: density functional theory (DFT) is an important example of a method which discards the model.

A fundamental application of electron configurations is in the interpretation of atomic spectra. In this case, it is necessary to convert the electron configuration into one or more term symbols, which describe the different energy levels available to an atom. Term symbols can be calculated for any electron configuration, not just the ground-state configuration listed in tables, although not all the energy levels are observed in practice. It is through the analysis of atomic spectra that the ground-state electron configurations of the elements were experimentally determined.

See also

- Atomic electron configuration table

- Electron configurations of the elements (data page)

- Periodic table (electron configurations)

- Atomic orbital

- Energy level

- Term symbol

- Molecular term symbol

- HOMO/LUMO

- Periodic Table Group

- d electron count

- Extension of the periodic table beyond the seventh period Discusses the limits of the periodic table

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 IUPAC Gold Book internet edition: "configuration (electronic)".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 In formal terms, the quantum numbers n, l and ml arise from the fact that the solutions to the time-independent Schrödinger equation for hydrogen-like atoms are based on spherical harmonics.

- ↑ IUPAC Gold Book internet edition: "Pauli exclusion principle".

- ↑ The full form of the configuration notation is a mathematical product, so 3p3 indicates that it is the cube of the 3p function which enters into the product (even if it is not normal to pronounce it in that way).

- ↑ Bohr, Niels (1923). "Über die Anwendung der Quantumtheorie auf den Atombau. I.". Z. Phys. 13: 117.

- ↑ Stoner, E.C. (1924). "The distribution of electrons among atomic levels". Phil. Mag. (6th Ser.) 48: 719–36.

- ↑ Pauli, Wolfgang (1925). "Über den Einfluss der Geschwindigkeitsabhändigkeit der elektronmasse auf den Zeemaneffekt". Z. Phys. 31: 373. doi:10.1007/BF02980592. English translation from Scerri, Eric R. (1991). "The Electron Configuration Model, Quantum Mechanics and Reduction". Br. J. Phil. Sci. 42 (3): 309–25. doi:10.1093/bjps/42.3.309. http://www.chem.ucla.edu/dept/Faculty/scerri/pdf/BJPS.pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Madelung, Erwin (1936). Mathematische Hilfsmittel des Physikers. Berlin: Springer.

- ↑ IUPAC Gold Book internet edition: "aufbau principle".

- ↑ Wong, D. Pan (1979). "Theoretical justification of Madelung's rule". J. Chem. Ed. 56 (11): 714–18. doi:10.1021/ed056p714. http://jchemed.chem.wisc.edu/Journal/Issues/1979/Nov/jceSubscriber/JCE1979p0714.pdf.

- ↑ The similarities in chemical properties and the numerical relationship between the atomic weights of calcium, strontium and barium was first noted by Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner in 1817.

- ↑ Scerri, Eric R. (1998). "How Good Is the Quantum Mechanical Explanation of the Periodic System?". J. Chem. Ed. 75 (11): 1384–85. doi:10.1021/ed075p1384. http://www.chem.ucla.edu/dept/Faculty/scerri/pdf/How_Good_is.pdf. Ostrovsky, V.N. (2005). "On Recent Discussion Concerning Quantum Justification of the Periodic Table of the Elements". Foundations of Chemistry 7 (3): 235–39. doi:10.1007/s10698-005-2141-y. http://www.springerlink.com/content/p2rqg32684034736/fulltext.pdf. Abstract.

- ↑ Electrons are identical particles, a fact which is sometimes referred to as "indistinguishability of electrons". A one-electron solution to a many-electron system would imply that the electrons could be distinguished from one another, and there is strong experimental evidence that they can't be. The exact solution of a many-electron system is a n-body problem with n ≥ 3 (the nucleus counts as one of the "bodies"): such problems have evaded analytical solution since at least the time of Euler.

- ↑ There are some cases in the second and third series where the electron remains in an s-orbital.

- ↑ Melrose, Melvyn P.; Scerri, Eric R. (1996). "Why the 4s Orbital is Occupied before the 3d". J. Chem. Ed. 73 (6): 498–503. doi:10.1021/ed073p498. http://jchemed.chem.wisc.edu/Journal/Issues/1996/Jun/jceSubscriber/JCE1996p0498.pdf. Abstract.

- ↑ Meek, Terry L.; Allen, Leland C. (2002). "Configuration irregularities: deviations from the Madelung rule and inversion of orbital energy levels". Chem. Phys. Lett. 362 (5–6): 362–64. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(02)00919-3. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6TFN-46G4S5S-1&_user=961305&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000049425&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=961305&md5=cef78ae6aced8ded250c6931a0842063.

- ↑ IUPAC Gold Book internet edition: "relativistic effects".

- ↑ Pyykkö, Pekka (1988). "Relativistic effects in structural chemistry". Chem. Rev. 88: 563–94. doi:10.1021/cr00085a006.

- ↑ The labels are written in lowercase to indicate that the correspond to one-electron functions. They are numbered consecutively for each symmetry type (irreducible representation in the character table of the point group for the molecule), starting from the orbital of lowest energy for that type.

References

- Jolly, William L. (1991). Modern Inorganic Chemistry (2nd Edition ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. : 1–23. ISBN 0-07-112651-1.

- Eric Scerri, The Periodic System, Its Story and Its Significance, Oxford University Press, New York, 2007.